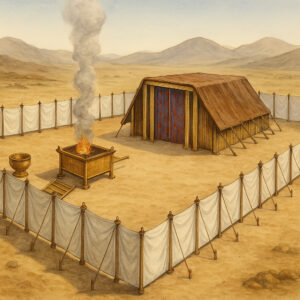

Parashat Pekudei culminates in the powerful image of God’s presence filling the Mishkan, marking the spiritual success of the Israelites’ labor. While the detailed description of the Sanctuary may seem excessive for a temporary structure, its deeper purpose is revealed through thematic and linguistic parallels to the Genesis creation narrative. These include mirrored expressions, structural patterns of sevens, and a literary chiasmus linking the beginning of Genesis with the end of Exodus.

Whereas Genesis recounts God creating a home for humanity, Exodus concludes with humanity creating a home for God. The Mishkan thus becomes not merely a physical space but a theological and existential statement about holiness. Drawing on Rabbi Isaac Luria’s concept of tzimtzum, Rabbi Sacks explains that chol—the secular—is the space God withdraws from to allow human freedom, while kodesh—the sacred—is the space humans create for God’s presence through self-limitation and devotion.

The Torah’s lengthy detail emphasizes that the Sanctuary was constructed exactly as God commanded, highlighting that holiness arises not from human invention but from submission to Divine will. The implications of tzimtzum extend far beyond the Mishkan: they inform our relationships, leadership, teaching, and love. Holiness is not about dominance or expression, but about restraint and the creation of space—for God, for others, and for transcendence.